The electric scooter market is zooming. Will profits catch up?

The electric scooter market is zooming. Will profits catch up?

Investors are pouring their money into electric scooter companies like Bird, one of the fastest-growing startups in history.

Marketed as eco-friendly alternatives to cars, scooters can help urban consumers bridge the “first and last mile,” the short distance between commuters’ homes and workplaces and larger transportation hubs, such as bus terminals or subway stations.

WATCH: Why the rise of the electric scooter has been a bumpy ride

The scooters are already on the streets in dozens of cities in the U.S., Canada and Europe. Bird, the first of the major electric scooter companies to launch in the U.S., is valued at $2 billion.

But will all the hype — and billions of dollars in investment — be supported by the business model?

That depends on whom you ask and what numbers you are using. Data leaked to The Information shows Bird has a 19 percent profit margin on its scooters, but that does not cover the cost of replacing the scooters or the cost of management and advertising. Adding those in could make the entire business unprofitable.

So how is a company like Bird valued at $2 billion?

The same question could be asked of electric car company Tesla, which is valued at $58 billion and has never had a profitable year. Or Twitter, which is valued at $25 billion, but only had its first profitable quarter in its 12-year history in February.

Sometimes, “the math doesn’t make sense,” said Harry Alford, the co-founder of the venture development firm Humble Ventures.

The main reason for the disconnect is that investors are betting on future profits, not what a company is making today.

Alford said when companies are just getting off the ground, there are often no profits to assess. Instead, investors look at the quality of three things: the management team, the current product and the market for that product.

When competition is fierce

The market for a product is key. So is being the first to market.

“You really have to think about where you are going to be distributing your product or service before the incumbents figure out what you are even doing,” Alford said.

The scooter market is a good example. Bird launched its scooters in September of 2017. A host of companies–Lime, Scoot, Spin, Lyft and Uber–quickly followed suit, debuting their own two-wheeled ventures this year. (Uber operates JUMP scooters and recently bought a share of Lime. Ford Motor Company announced this week it is buying Spin.)

Now it’s a battle to see who can grab the most market share as companies drop thousands of scooters on the streets for consumers to try.

Bird and Lime operate in dozens of mid- to large-sized cities across the country. JUMP and Lyft’s operations are limited to a few locations.

The companies’ markets often overlap, creating fierce competition. All four companies operate in Santa Monica, California, for example.

“These are network businesses whose competitiveness improves with scale,” i.e. increasing the size of the operation, said Juan Matute, the deputy director of the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies.

The more scooters a company has on the street, the more likely people are to use that company’s app on a regular basis, and that builds customer loyalty, which boosts profits.

When the profits don’t come in

But expansion does not automatically mean profit. Often, the profits never come.

Investors lose trust that they will make their money back and stop injecting capital, the cash needed to operate its business drys up and the company goes belly up.

This is not at all unusual. After all, nine out of 10 startups fail.

Plus, all of those scooters also come with liabilities, which the companies, and their investors, must take into consideration.

San Francisco and Denver temporarily banned scooters until they could establish regulations.

Bird and Lime have been named in a class-action lawsuit that alleges their negligence led to both riders and pedestrians being injured.

So far, investors still see the potential for profit despite the setbacks.

Keeping an eye on the next big thing

Investors are also looking for companies that are forward-thinking. Remember, the value of a company is all about the future — future profits, that is.

Bird has told investors it is looking for ways to boost its profit margins by reducing the cost of charging the electric-powered scooters and by lengthening the lifespan of the scooters, which cost about $550 each to replace based on The Information’s data.

Lyft and Uber, which are both planning to go public next year, jumped into the scooter market when they saw the potential for profits.

Andrew Savage, the vice president at Lime, told the PBS NewsHour that its business model has been focused on solving the “first and last mile” transportation issues. But he said Lime is already looking down the road to deliver a “second and third mile” solution.

“We’re still a young company. We’re still evolving and developing new products that will help solve the suite of issues that cities are facing around the country and globe,” Savage said.

Lime announced this week that it is launching a car-share program in Seattle.

Valuations are different for private companies as opposed to those publicly owned on the stock exchange. A publicly owned company’s “market cap” valuation, which is based on its stock price and is calculated differently than private company valuations, can change daily.

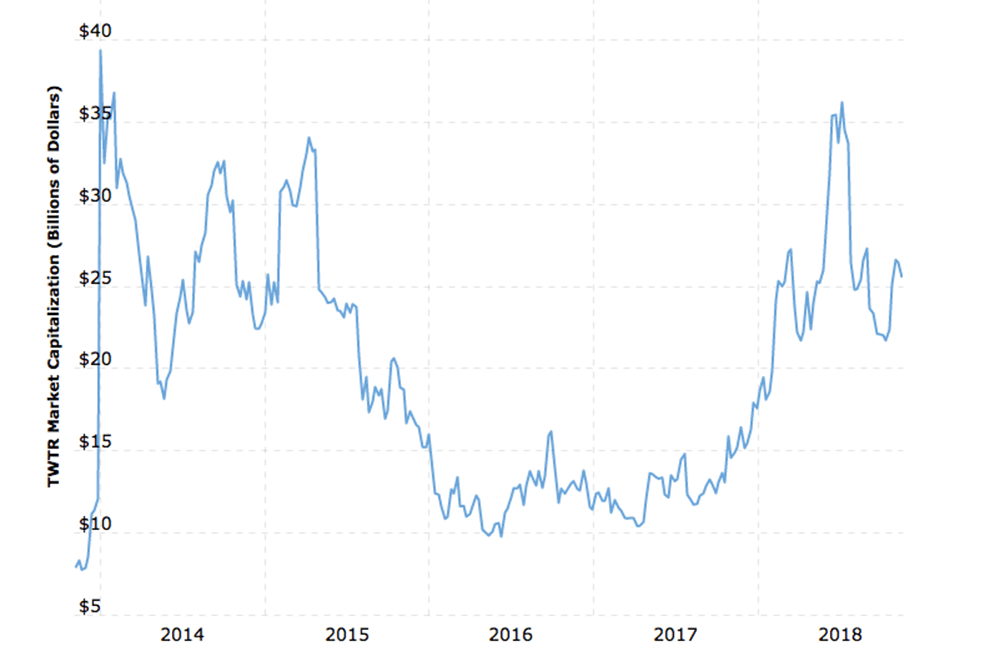

Take this Macro Trends chart of Twitter’s market cap for example:

The value changes when stockholders react to any kind of news they think could benefit or hurt the company’s future profits. A quarterly earnings report that shows a company is bringing in more revenue, for example, might give investors more incentive to buy the stock and boost the company’s value.

Alford cautions that even long stretches of losses do not mean entrepreneurs and investors should throw in the towel.

“In those situations, you keep trying to iterate and pivot until you find out that sustainable solution,” he said.

That could take years — 12 in the case of Twitter. But, in the end, investors are betting it will be worth the wait.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!